Wi-Fi has become an essential part of everyday life, and every single business of any size is pretty much guaranteed to have one or more Wi-Fi networks operating in its facilities. Wi-Fi is also a prime target for threat actors, and if not properly secured, it can be a major risk for your organization’s security.

When setting up a wireless router or access point, you are provided with several security standards to apply to your Wi-Fi network. These standards have varying degrees of security, and some should be explicitly avoided.

Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP): WEP is an outdated security standard released in 1997 and completely abandoned in 2004. WEP aimed to assure the same level of security as a wired connection, hence the name. WEP used a single 64 or 128-bit key, meaning that only one key was used for all network traffic. As you can see from this description, WEP became insecure very quickly and is not recommended in any way for today’s networks.

Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA): WPA was introduced in 2003 and implemented 256-bit keys and the Temporal Key Integrity Protocol (TKIP), which changed the keys that different systems use. This was a good deal more secure than the static key used in WEP. TKIP was later replaced with the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). WPA also introduced Message Integrity Checking to ensure that traffic had not been altered by threat actors. Vulnerabilities in WPA were soon uncovered, and just like WEP, it is not recommended for use today.

Wi-Fi Protected Access 2 (WPA2): Introduced in 2004, very quickly after WPA, WPA2 uses the robust security network (RSN) mechanism and provides more control over the method used to implement Wi-Fi connections. WPA2 has two deployment options:

- WPA2-PSK: Uses a pre-shared key for authentication to the network. This is the traditional method of deploying Wi-Fi, allowing anyone to connect to the network if they have the pre-set password or passphrase.

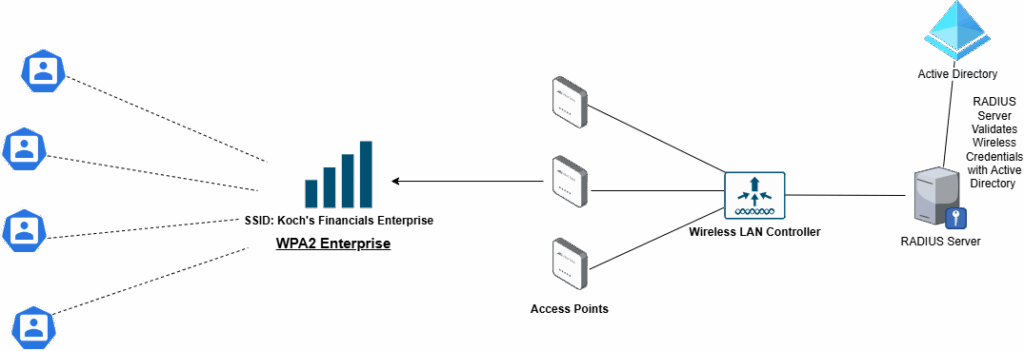

- WPA2-Enterprise: This is a business-oriented standard that allows administrators to set up 802.1x authentication through a RADIUS server. Essentially, this allows employees to connect to the Wi-Fi using a personal username and password. This helps with organization and can reduce the attack surface of your Wi-Fi, especially if combined with MAC Address Filtering or Network Access Control (NAC). RADIUS needs to be pre-configured with user credentials hosted on a separate server. There are proprietary and free options for RADIUS Servers. You could also set up your network to use credentials from other identity sources, such as Active Directory. Going the WPA2-Enterprise route requires a bit more work than a PSK deployment; thus, you should plan carefully before attempting to implement it.

Wi-Fi Protected Access 3 (WPA3): WPA3 implements several encryption features that offer improved security to WPA2. The SAE Protocol is implemented in WPA3, which is a replacement for WPA2’s PSK. SAE allows much stronger security for the key exchange. While the PSK method of WPA2 may be more straightforward, it is vulnerable to dictionary attacks. WPA2’s 802.1x Enterprise authentication method is also less secure than WPA3’s. WPA3 Enterprise uses 192-bit encryption compared to 128-bit encryption for WPA2 Enterprise.

WPA3, by design, offers mitigation for brute force and dictionary attacks that WPA2 is more vulnerable to. WPA3 involves the network infrastructure with each password attempt, making it harder for attackers to simply sit back and run a password file against the Wireless Network. WPA3’s encryption also offers secure encryption to Open networks, a common target for wireless attacks in previous versions of WPA.

WPA3’s SAE uses solid forward secrecy for the initial key exchange. This prevents the data from being captured and then decrypted in the future because there is a new, unique private key for each network transaction. WPA2’s 4-way handshake does not employ stellar forward secrecy, so if a private key is captured in the future, attackers can return to their compiled packets and decrypt them. SAE is resistant to offline dictionary attacks because both the Host and the AP authenticate simultaneously during a transmission using unique cryptographic keys every time.

Open Wi-Fi offers no security, allowing any party to connect and receive wireless access. WPA2-PSK uses a Pre-Shared Key known to both the Host and AP. It employs the AES encryption protocol with 128-bit keys to encrypt sessions. Finally, OWE eliminates PSKs and instead utilizes a Diffie-Hellman key exchange to establish uniquely encrypted sessions between the Host and AP.

When a user connects to an OWE-enabled network, that node is issued a unique encryption key by the AP. The host and AP engage in a Diffie-Hellman key exchange in which the encryption key is acknowledged by the host. Once this exchange is complete, the unique private key is used to confirm the session between the host and AP until the session is terminated. OWE being encrypted open is a strength as it bolsters the strength of open guest networks, creating a better experience for both network admins and guest users. A downside of this is that it is still being used on an Open network, meaning that attackers still can connect and possibly perform attacks on the network that OWE is not meant to address. WPA3 also provides the option for Enterprise security, allowing employees to connect through 802.1x. Network admins can decide if they want to use passwords or certificates to authenticate via Enterprise. In WPA3 Enterprise, server certificate validation is used to keep the end user authenticated securely.